Migraine: An In-Depth Overview of a Complex Neurological Disorder

Introduction

Migraine is far more than just a “bad headache.” It is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of moderate to severe headache, often accompanied by a range of sensory disturbances such as nausea, vomiting, visual disturbances, and heightened sensitivity to light, sound, and smell. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), migraine is among the top 10 most disabling medical conditions worldwide, significantly affecting an individual’s quality of life, productivity, and mental well-being.

The impact of migraine extends beyond the physical pain—it can disrupt daily activities, strain social relationships, and impose a substantial economic burden on both individuals and healthcare systems. Understanding migraine in depth requires exploring its complex pathophysiology, identifying triggers and risk factors, and discussing both treatment and preventive strategies.

Pathophysiology of Migraine

The pathophysiology of migraine is intricate and still not fully understood, but advances in neuroscience have shed light on its underlying mechanisms. It is now recognized as a neurovascular disorder involving complex interactions between the brain, blood vessels, and the trigeminal nerve system.

1. Cortical Spreading Depression (CSD)

- Definition: CSD refers to a wave of neuronal and glial depolarization that slowly propagates across the cerebral cortex.

- Role in Migraine: This phenomenon is thought to be responsible for migraine aura—neurological symptoms such as visual disturbances or sensory changes that occur before the headache phase. CSD triggers the release of inflammatory mediators and alters blood flow in the brain.

2. Trigeminovascular System Activation

- The trigeminal nerve is a major sensory nerve of the face and head.

- During a migraine, activation of trigeminal nerve fibers causes the release of vasoactive neuropeptides, including calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), substance P, and neurokinin A.

- These neuropeptides lead to neurogenic inflammation, vasodilation of cerebral blood vessels, and increased pain sensitivity.

3. Role of CGRP

- CGRP is now considered a key player in migraine pathophysiology.

- It causes dilation of intracranial blood vessels and enhances pain transmission.

- Elevated levels of CGRP have been detected during migraine attacks, and blocking CGRP or its receptor has become an important therapeutic strategy.

4. Brainstem Dysfunction

- Brain imaging studies suggest that migraine involves hyperexcitability of certain brainstem nuclei, including the dorsal raphe nucleus, locus coeruleus, and periaqueductal gray.

- These regions are involved in pain modulation and autonomic control, explaining associated symptoms like nausea and photophobia.

5. Genetic Component

- Migraine is strongly influenced by genetics. Mutations in ion channel genes (such as CACNA1A in familial hemiplegic migraine) can alter neuronal excitability, predisposing individuals to attacks.

In summary, migraine is the result of abnormal brain excitability, neurovascular dysregulation, and inflammatory mediator release—making it a truly multifaceted neurological condition.

Causes and Triggers of Migraine

While the exact cause of migraine is rooted in neurovascular dysfunction and genetic predisposition, triggers play a crucial role in precipitating individual attacks. Triggers vary from person to person, but some are consistently reported.

1. Hormonal Changes

- Particularly in women, fluctuations in estrogen levels—such as during menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause—are strongly linked to migraine attacks.

- Menstrual migraine occurs in the days just before or during menstruation due to a drop in estrogen.

2. Dietary Factors

- Certain foods and drinks are common triggers:

- Aged cheeses (tyramine content)

- Caffeine overuse or withdrawal

- Chocolate

- Red wine and alcohol

- Processed meats with nitrates

- Artificial sweeteners (aspartame)

3. Environmental Factors

- Bright or flickering lights

- Loud noises

- Strong odors (perfumes, chemicals)

- Sudden weather changes or barometric pressure shifts

4. Lifestyle-Related Triggers

- Sleep deprivation or oversleeping

- Skipping meals or fasting

- Stress and anxiety

- Excessive screen time without breaks

5. Medications

- Certain vasodilators like nitroglycerin

- Oral contraceptives

- Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

Risk Factors for Migraine

Not everyone exposed to triggers develops migraine. Specific risk factors increase susceptibility:

- Genetics

- Migraine often runs in families; having a first-degree relative with migraine increases risk significantly.

- Gender

- Women are about three times more likely than men to experience migraines, largely due to hormonal influences.

- Age

- Migraine often begins in adolescence or early adulthood, with peak prevalence between ages 20–40.

- Medical Conditions

- Depression, anxiety, epilepsy, sleep disorders, and hypertension are associated with increased migraine risk.

- Obesity

- Chronic migraine is more common in individuals with obesity, possibly due to inflammatory and vascular changes.

Clinical Features and Stages of Migraine

Migraines typically occur in four stages, though not everyone experiences all stages.

- Prodrome Phase (Hours to Days Before)

- Symptoms: mood changes, food cravings, neck stiffness, increased urination, fatigue.

- Significance: Recognizing prodrome can help initiate early treatment.

- Aura Phase (Optional)

- Occurs in about 25% of migraine patients.

- Symptoms: visual disturbances (flashing lights, zigzag lines), sensory changes (numbness, tingling), speech difficulties.

- Duration: Usually 5–60 minutes.

- Headache Phase

- Pain is typically unilateral, throbbing, and worsened by activity.

- Accompanied by nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia.

- Duration: 4–72 hours.

- Postdrome Phase

- Symptoms: fatigue, irritability, difficulty concentrating, mild residual headache.

- Sometimes referred to as a “migraine hangover.”

Diagnosis of Migraine

Diagnosis is clinical, based on patient history and symptom patterns, according to International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) criteria.

Typical diagnostic features:

- At least five attacks fulfilling:

- Headache lasting 4–72 hours (untreated or unsuccessfully treated)

- At least two of: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate/severe intensity, aggravation by routine activity

- At least one of: nausea/vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia

Investigations (like MRI/CT scans) are usually reserved for atypical presentations to rule out secondary causes.

Treatment of Migraine

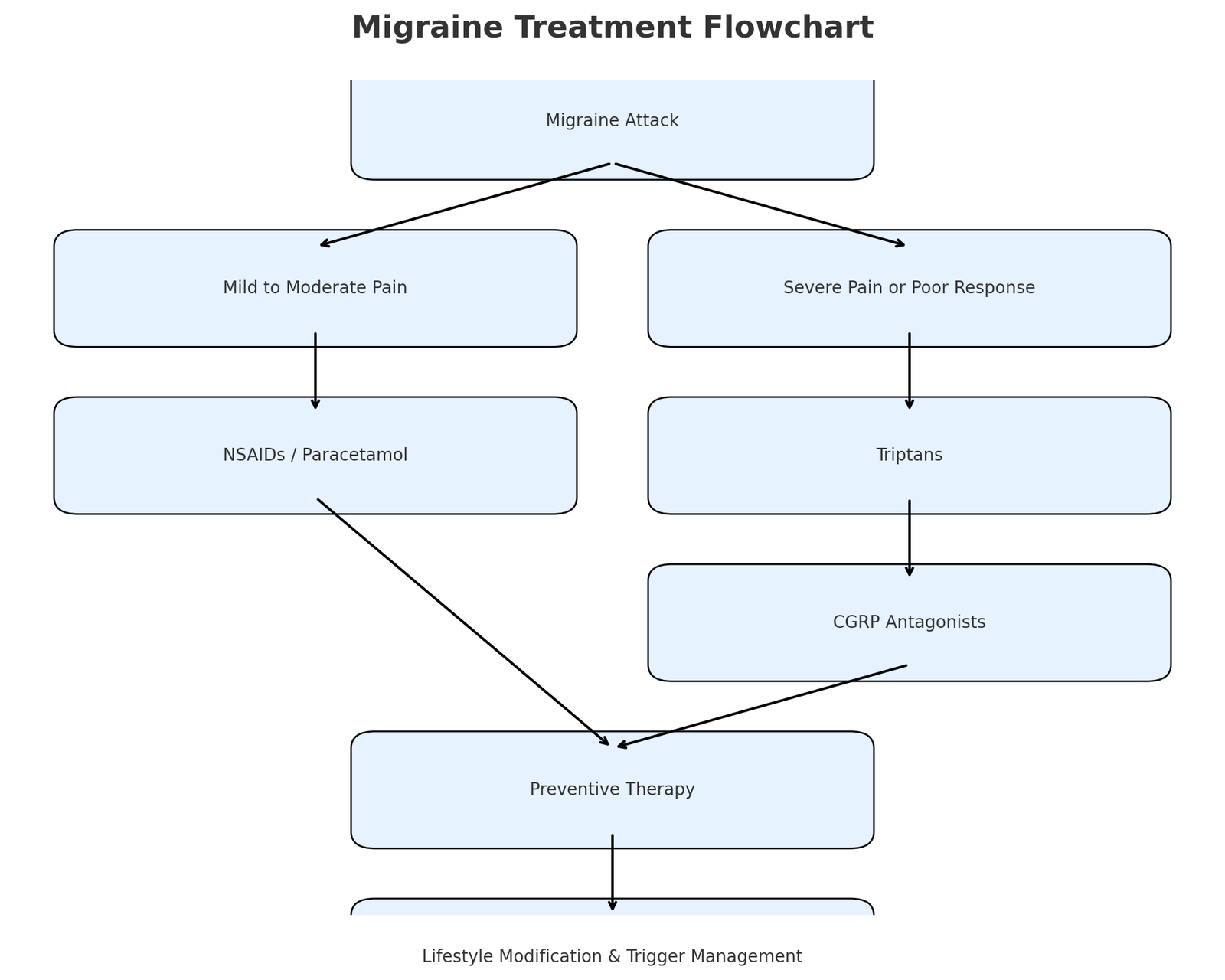

Management of migraine involves acute (abortive) treatment for attacks and preventive (prophylactic) treatment to reduce frequency and severity.

A. Acute Treatment

Goal: Relieve pain and associated symptoms quickly.

- Analgesics

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen)

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for mild attacks

- Triptans (Serotonin 5-HT1B/1D receptor agonists)

- Sumatriptan, Rizatriptan, Zolmitriptan

- Effective in aborting attacks by constricting blood vessels and inhibiting neuropeptide release

- Ergot Alkaloids

- Ergotamine, Dihydroergotamine (less commonly used due to side effects)

- Antiemetics

- Metoclopramide, Domperidone (help with nausea and improve drug absorption)

- CGRP Antagonists

- Ubrogepant, Rimegepant (newer drugs for acute migraine treatment)

B. Preventive Treatment

Indicated if:

- Frequent attacks (≥4 per month)

- Severe attacks causing significant disability

- Poor response to acute therapy

- Beta-Blockers

- Propranolol, Metoprolol

- Antidepressants

- Amitriptyline (tricyclic), Venlafaxine (SNRI)

- Anticonvulsants

- Topiramate, Valproic acid

- CGRP Monoclonal Antibodies

- Erenumab, Fremanezumab, Galcanezumab

- Lifestyle and Trigger Management

- Regular sleep, hydration, balanced diet, stress reduction

Non-Pharmacological Therapies

- Biofeedback and Relaxation Techniques

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Acupuncture

- Regular Aerobic Exercise

- Yoga and Meditation

Prevention Strategies

Prevention focuses on trigger avoidance, lifestyle changes, and adherence to preventive therapy.

- Maintain a Migraine Diary

- Helps identify and avoid personal triggers.

- Sleep Hygiene

- Consistent sleep schedule, avoiding late nights.

- Dietary Management

- Avoid known dietary triggers, eat balanced meals on time.

- Stress Management

- Mindfulness, relaxation exercises, and planned breaks during work.

- Physical Activity

- Regular moderate exercise improves vascular health and reduces attack frequency.

Complications of Migraine

Although most migraines are benign, some can lead to serious complications:

- Status migrainosus: Severe migraine lasting >72 hours

- Migraine with brainstem aura

- Persistent aura without infarction

- Migrainous infarction (stroke triggered by migraine)

Conclusion

Migraine is a complex neurological disorder with significant personal and societal impact. Its pathophysiology involves intricate neurovascular interactions, genetic predisposition, and abnormal brain excitability. Effective management requires a combination of acute treatments, preventive strategies, and lifestyle modifications tailored to each patient. With advances in research—particularly in CGRP-targeted therapies—migraine care is entering an era of more precise and personalized medicine.

By raising awareness, encouraging early diagnosis, and promoting holistic care approaches, we can significantly reduce the burden of this disabling condition.

For more regular updates you can visit our social media accounts,

Instagram: Follow us

Facebook: Follow us

WhatsApp: Join us

Telegram: Join us